a tale of two diners

New owners have stepped in to revive Kellogg's and Three Decker, reimagining the role of diners in today's restaurant landscape.

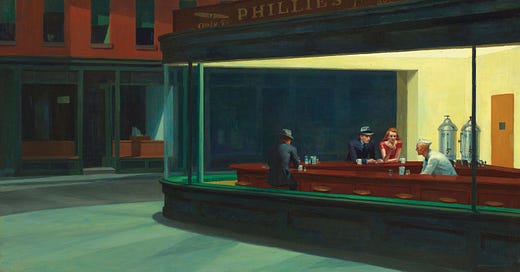

What constitutes a diner? To me, it’s a place you can visit at anytime of day, order practically anything you want, and linger. An equalizer of sorts, just like the New York City subway, where people of all walks of life sit side-by-side at the counter, sipping their coffee.

Diners are slowly dissipating from the forefront of the city’s dining scene. Historic establishments have struggled to keep up with the rising rent and food costs while staying true to the low prices that define them. Restaurant groups and chefs have stepped in, updating the menus and reupholstering the ripped vinyl booths, hoping to resurrecting these beloved institutions — or at the very least, keep them from closing their doors.

It’s a city-wide shift. In the past two years alone, I’ve seen this happen at Montague Diner in Brooklyn Heights, S&P Lunch in Flatiron, Three Decker Diner in Greenpoint, and most notably, the nearly 100-year-old Kellogg’s Diner in Williamsburg.

I appreciate how the new owners want to keep these diners a constant in the neighborhoods they serve. But, like others, I was initially hesitant when I heard that the owner of Variety Coffee Roasters took over my local joint, Three Decker Diner. Improvements were made, like switching to buzzers to signal when a table is ready instead of forcing guests to stand by the door, while the quirks that felt inherent to the diner, like the host manning the waitlist with her dark, drawn-on eyebrows with her bleach-blonde hair, remained the same.

I’d consider myself more of a regular now than before ownership changed. Maybe it’s because the bones of Three Decker are there — the book-length menu, unlimited coffee refills, the familiar staff — but the kinks were ironed out. The spiral-bound menu was updated with custom graphics to replace the generic stock images of the Manhattan skyline. There’s more variety too, including a whole section of Tex-Mex favorites with burritos, tacos, and huevos rancheros. The best change though was the switch to Variety drip coffee, which is significantly better and $1 with unlimited refills.

Three Decker is a place I can visit any time of day to fulfill any need. Hungover on Sunday? I’ll go for a breakfast burrito with beans. Late-night dinner? A chicken Caesar wrap and a black and white milkshake. Afternoon lunch? A roast turkey sandwich with waffle fries and Diet Coke. I can go with a group of friends and we can each find something we want to eat. And every time I walk away with a bill that’s about $20 or less — in line with my receipts prior to the new ownership.

While Kellogg’s owners took a similar approach to Three Decker, it landed different. Is it a scene-y New York City restaurant? Or is it a diner? As it stands, I’m not entirely sure. Three Decker gets it, and distinctly falls into the latter category, whereas Kellogg’s seems to straddle the line between the two.

The most dramatic change that signaled my suspicions was the new reservation system. I’ve attempted to walk into Kellogg’s a handful of times since opening, usually after the dinner rush, around 9 p.m. to 11 p.m., and have scored a table twice. Other factors, like the full-blown cocktail menu and pastry chef on staff, make me question if Kellogg’s can really be considered a diner.

Like Three Decker, Kellogg’s brings a Tex-Mex influence to its updated menu with dishes like a guajillo-braised short rib hash alongside elevated takes on diner classics like skate wing almondine. These changes led to a much smaller menu, now just a double-sided sheet of paper, at a higher price point. For example, a standard burger is $18 with a measly side of fries, $4 more than one around the same size at Three Decker.

If Kellogg’s is aiming to be a place that’s a more refined, upscale version of its former self, then the execution isn’t there. The food is inconsistent and overpriced. During one visit, the onions on my burger were grilled, while on another, they were completely raw. My order of Texas chili arrived to the table cold, needing more sour cream and pickled red onions to combat the dryness of the braised beef. As for the service, on two separate occasions, the same server brought me the check from a different table. My bills averaged $36, which is 50 percent more than a typical visit to Three Decker.

Some characteristics of a classic diner are present; Kellogg’s is open 24 hours a day and there’s a dessert case filled with pretty, mid-century-looking treats. The dining room also got a much-needed upgrade with sleek, retro pink walls and booths, but it’s missing that lived-in, nostalgic feel that Three Decker perfectly encapsulates.

Its worth noting that the previous Kellogg’s owners filed for bankruptcy — a reminder that diners must adapt to survive in New York, especially in a climate where eggs are around $7 a dozen. Yet, the new iteration of Kellogg’s feels like an imitation of its past, a caricature of a classic diner. Three Decker proves that survival doesn’t require following trends or overcomplicating things; modernization can embody the spirit of its old self.

If the new owners and chefs that come in practice restraint, and try not to get too cheffy with the menus, I believe these revamped diners can remain fixtures in the city. Still, the bigger question stands: is it a diner if the first thing you’re asked when you walk through the door is “do you have a reservation?”

— Rayna